Anatomy

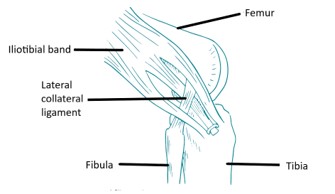

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of four major ligaments that stabilizes the knee joint. A ligament is a tough band of fibrous tissue, similar to a rope, which connects the bones together at a joint. There are two ligaments on the sides of the knee (collateral ligaments) that give stability to sideways motions: the medial collateral ligament (MCL) on the inner side and the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) on the outer side of the knee. Two ligaments cross each other (therefore, called “cruciate”) in the center of the knee joint: The crossed ligament toward the front (anterior) is the ACL and the one toward the back of the knee (posterior) is the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL).

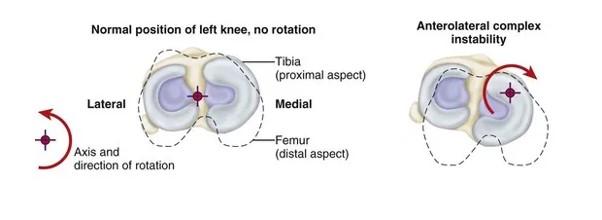

The ACL prevents the lower bone (tibia) from sliding forward too much and stabilizes the knee to allow cutting, twisting and jumping sports. The PCL stops the tibia from moving backwards.

HOW CAN THE ACL TEAR?

The most common mechanism that tears the ACL is the combination of a sudden stopping motion on the leg while quickly twisting on the knee. This can happen in a sport such as basketball, for example, when a player lands on the leg when coming down from a rebound or is running down the court and makes an abrupt stop to pivot. In football, soccer, or lacrosse, the cleats on the shoes do not allow the foot to slip when excess force is applied. In skiing, the ACL is commonly injured when the skier sits back while falling. The modem ski boot is stiff, high, and is tilted forward. The boot thus holds the tibia forward and the weight of the body quickly shifts backwards. Thus, too much force is suddenly applied to the knee. The excess force causes the ACL to” pop”.

A contact injury, such as when the player is clipped in football, forces the knee into an abnormal position. This may tear the ACL, MCL and other structures.

WHAT ARE THE SIGNS THAT AN ACL IS TORN

When the ACL tears, the person feels the knee go out of joint and often hears or feels a “pop”. If he or she tries to stand on the leg, the knee may feel unstable and give out. The knee usually swells a great deal immediately (within two hours). Over the next several hours, pain often increases and it becomes difficult to walk.

WHAT OTHER KNEE STRUCTURES CAN BE INJURED WHEN THE ACL TEARS?

The meniscus is a crescent shaped cartilage that acts as a shock absorber between the femur and tibia. Each knee has two menisci: medial (inner) and lateral (outer). The menisci are attached to the tibia. When the tibia suddenly moves forward and the ACL tears, the meniscus can become compressed between the femur and tibia tearing the meniscus. The abnormal motion of the joint can also bruise the bones.

There is a second type of cartilage in the knee joint called articular cartilage. This is a smooth, white glistening surface that covers the ends of the bones. The articular cartilage provides lubrication and as a result, there is very little friction when the joint moves. This joint cartilage can get damaged when the ACL tears and the joint is compressed in an abnormal way. If this articular cartilage is injured, the joint no longer moves smoothly. Stiffness, pain, swelling and grinding can occur. Eventually, arthritis can develop. The MCL and other ligaments in the joint can also be disrupted when the ACL tears. This is more common if an external blow to the knee caused the injury (such as if the knee was clipped while playing football) or when skiing.

WHAT IS THE INITIAL TREATMENT FOR A KNEE THAT MAY HAVE A TORN ACL?

The initial treatment of the injured joint is to apply ice and gentle compression to control swelling. A knee splint and crutches are typically used. The knee should be evaluated by a doctor to see which ligaments are torn and to be sure other structures such as tendons, arteries, nerves, etc. have not been injured. X-rays are taken to rule out a fracture. Sometimes an MRI is needed, but usually the diagnosis can be made by physical examination.

HOW WILL THE KNEE FUNCTION IF THE ACL IS TORN?

If no structure other than the ACL is injured, the knee usually regains it range of motion and is painless after six or eight weeks. The knee may feel “normal”. However, it can be a “trick knee”. If a knee has a torn ACL, the knee can give way or be unstable when the person pivots or changes direction. The athlete can usually run straight ahead without a problem but when he or she makes a quick turning motion, the knee tends to give way and collapse. This abnormal motion can damage the menisci or articular cartilage and cause further knee problems.

If a person does not do sports and is relatively inactive, the knee can feel quite normal even if the ACL is torn. Thus, in some older or less active patients, the ACL may not need to be reconstructed. In young, athletic patients, however, the knee will tend to reinjure frequently and give way during activities in which the person quickly changes direction. Therefore, it is usually recommended to reconstruct the torn ACL

Surgical reconstruction of the ACL

Reconstruction involves placing a graft inside the knee by arthroscopic surgery (keyhole). A>90% success rate is normal with some deterioration over time depending upon other damage within the joint.

Although ACL reconstruction surgery has a high probability of returning the knee joint to near normal stability and function, the end result for the patient depends largely upon a satisfactory rehabilitation and the presence of other damage within the joint.

Advice will be given regarding the return to sporting activity, dependant on the amount of joint dam- age found at the time of reconstructive surgery.

It is important to preserve damaged joint surfaces by restricting impact loading activity to delay the onset of degenerative osteoarthritis later in life.

In the surgery a graft will be harvested to use to reconstruct the torn ligament. Usually two of the hamstring tendons are taken, but sometimes other suitable graft choices are used. This will be discussed with you prior to the operation. The remnants of the torn ACL are removed with keyhole surgery and tunnels are made in the tibia (shin bone) and femur (thigh bone) to allow the graft to be positioned across the knee. The new reconstructed ligament is then fixed at both ends to secure it in place.

Graft choice

Some technical terminology:

Autograft – this is a piece of tissue taken from one part of the body and used elsewhere in a different part of the body.

Allograft – this is where a piece of tissue is donated from another person (as in the example of kidney or heart transplantation)

The most common way of performing an ACL reconstruction in Australia is to use autograft, ie. the patient’s own tissue. The two main options here are:-

Patellar tendon: a strip is taken from the middle of the patient’s patellar tendon, at the front of the knee, along with a small block of bone at either end.

Hamstring tendon: two long strips of tendon can be taken from the patient’s hamstrings, at the back of the thigh.

There have been lots of scientific studies looking at whether hamstring tendons are better than patellar tendon grafts, or vice versa. The overall analysis confirms that good outcomes can be obtained with both choices. Patellar tendon grafts have the advantage that they may heal and become more firmly fixed a little quicker than hamstring grafts and their size and shape may be a little more predictable. The downside of having a patellar tendon graft is that taking the graft requires an incision (scar) at the front of the knee. Some patients can suffer ongoing pain at the front of the knee and discomfort kneeling after an ACL reconstruction if a patellar tendon graft has been used.

When a hamstring graft is used, a relatively thin strip of tendon is taken from the back of the knee/thigh. Two tendons are usually taken; the gracilis and the semitendinosis. These two are sewed together and then the strips are folded in half, giving 4 strands of tendon, which provides enough strength to replace the missing ACL. Newer modern devices for fixing the tendon in place give extremely strong fixation. The loss of the hamstring tendons from the back of the knee causes some loss of hamstring strength initially after the operation. However, the rest of the hamstrings very rapidly compensate during the post-operative rehabilitation period so that soon no actual weakness can be noticed.

Allografts

Allograft tissue is tissue that has been obtained from a tissue donor. These tendons are harvested after death from people who have asked for their bodies to be available for organ donation.

Donors are screened very carefully screened to exclude individuals from any high risk category for carrying any kind of infection. Blood samples are taken to check for the presence of bacterial or viral infections. The tissue is taken by an aseptic technique, meaning that it is removed from the donor in a sterile fashion (in the same way that surgery is performed in an operating theatre).

The tissue graft itself is then tested for a very wide variety of diseases, bacteria and viruses. Any positive results mean that the tissue will be discarded.

Tissue that has cleared this process is then subjected to a sterilisation process. The grafts are then frozen and stored in an accredited Tissue Bank. The freezing process helps sterilise the tissue even further.

We generally use allografts only for multiple ligament surgery. There is fairly strong evidence that allografts used for anyone under the age 35 have a higher rate of failure than comparable autografts.

Adapted with permission from https://orthoinfo.aaos.org